| RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology

(CDB) 2-2-3 Minatojima minamimachi, Chuo-ku, Kobe 650-0047, Japan |

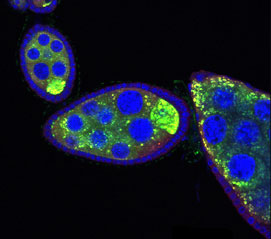

January 13, 2004 – In many species, the reproductive cells of the germline can only form properly if certain mRNAs are prevented from translating into proteins until they have been transported to precise target locations in the egg and the appropriate developmental stage has been reached. In a study published in the January issue of Developmental Cell, members of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology (CDB) Laboratory for Germline Development (Akira Nakamura, Team Leader) report that, in the fruit fly Drosophila, this translational repression is achieved by a newly identified complex formed by three associating proteins.

RNA activity during Drosophila oogenesis involves a number of sequential processes.

The Drosophila oocyte share cytoplasm with neighboring nurse cells via an incomplete

cell membrane, allowing mRNAs and proteins from the nurse cells to be transported to the

oocyte in the form of ribonucleoproteins. Following their export from the nurse cell nuclei,

mRNAs are translationally repressed, or ‘masked,’ and transported to specified

regions of the oocyte, where they establish fixed and precise localizations and regain their

ability to undergo translation. In one example of this critically important regulation,

the translation of the RNA for the maternal gene oskar, which has critical functions

in embryonic patterning and the formation of germline cells, is repressed during its transport

to the posterior pole of the oocyte. This transcript-specific repression is known to be

mediated by the protein Bruno, which binds to the 3’ UTR of oskar mRNA, but

the underlying mechanisms have remained obscure.

In the Developmental Cell study, the Nakamura lab demonstrated that an ovarian protein, Cup, is another protein required to inhibit the premature translation of oskar mRNA, and that Cup achieves this by binding to a second protein, eIF4E, a 5’ cap-binding general translation initiation factor. The binding with Cup prevents eIF4E from binding with a different partnering molecule, eIF4G, and thereby inhibits the initiation of translation. Findings that a mutant form of Cup lacking the sequence with which it binds eIF4E failed to repress oskar translation in vivo, that Cup interacts with Bruno in a yeast two-hybrid assay, and that the Cup-eIF4E complex associates with Bruno in an immunoprecipitation assay, suggesting that these three proteins form a complex that achieves translational repression by interactions with both the 3' and 5' ends of the oskar RNA. A similar model of protein interactions is observed in the translational repression of the cyclin-B1 RNA in the Xenopus African clawed frog, indicating that the paradigm of translational repression through the 5'/3' interactions is conserved across species. Nakamura next intends to look into the means by which the repressor effects of the eIF4E-Cup-Bruno complex are alleviated at the appropriate developmental stage, after the oskar ribonucleoprotein complex has reached and anchored to its appropriate destination at the pole of the oocyte.

|

|||||

|

|||||

[ Contact ] Douglas Sipp : sipp@cdb.riken.jp TEL : +81-78-306-3043 RIKEN CDB, Office for Science Communications and International Affairs |

| Copyright (C) CENTER FOR DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY All rights reserved. |